On to Interior Design

On to Interior Design

Back to the Book Arts  On to Interior Design

On to Interior Design

Arts and Crafts in Midwestern Architecture

Arts and Crafts architecture would never have succeeded as a design concept if it had not also met the changing needs of society. American families in the twentieth century were different from nineteenth century families and they needed a different kind of home. Daily living had evolved to a routine where men left the home to work each day, and women stayed home to care for the children. Servants, once plentiful and cheap, became too expensive for the middle class and women assumed the role of sole homemaker..

Housing design had to adapt to this simplified lifestyle. There was no longer any requirement for large houses with formal entertaining areas, family areas, and servant areas. Music rooms, reception rooms, conservatories, parlors, and butler pantries were dropped in favor of "living rooms" and smaller kitchens. Because of increased street noise, Victorian front porches were no longer desirable and they were replaced with sun rooms, sleeping porches, and back screened porches.

Atthe time the lifestyles of Americans were changing, magazines like House Beautiful and Ladies' Home Journal were promoting Arts and Crafts home architectural styles to their female readers. The Prairie style and the bungalow not only appealed aesthetically to these women as the latest trend in home design, but they fit the requirement for simpler, smaller homes that could easily maintained without servants.

The bungalow became the most popular Arts and Crafts home design. Modeled after traditional homes in India and popularized in California, the bungalow was a low, functional, spreading house. It emphasized horizontal lines, overhanging roofs, simple porches, and bands of windows that brought the outside in. The bungalow was usually one or one and one-half stories tall, and was often marketed to beginning homeowners. Particularly small versions of the bungalow were called "bachelor's bungalows" or "workman's bungalows," and were only 600-800 square feet in size. Nearly everyone could afford such a simple house, and the style fit with America's democratic ideals. What these smaller versions lacked in space, they made up for in charm.

Gustav Stickley promoted a version of the bungalow in his magazine The Craftsman. The Craftsman bungalow tended to be larger, often two stories tall. Stickley retained the sloping roof line, oversized eaves, and window bands of the traditional bungalow, but relied more heavily on natural building materials like cedar shingles, stone fireplaces, and slate or tile roofs for a rustic look. He often incorporated a pergola on the side as a way to unite the outside and the inside. His interior designs were functional, without ornamentation, and often included built-ins like inglenooks around the fireplace. Stickley published many designs for such homes in his magazine, and in 1909 and 1912 published whole catalogs of Craftsman houses. In 1916 alone, he claimed that over $20 million in Craftsman-inspired homes were built.

The Prairie style was the brainchild of Chicago architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1900. Wright envisioned a home that would echo the long, low prairie that stretched beyond Chicago's city limits. The design was Wright's conscious effort to create a distinctly American style of architecture. While American, the Prairie home borrowed many Japanese elements, including clean, geometric lines.

The Prairie home was an extension of the bungalow design in many ways, but it was much more expensive to build. First of all, it was greater in size and expanded out in long horizontal wings, thus it required larger lots. There were few standardized plans for Prairie houses, and the complicated designs required on-site architects and precise building techniques. For these reasons, the Prairie design was built primarily for the upper-classes, and did not influence vernacular architecture to the extent that the bungalow did.

The expanding pre-war economy led to an expanding middle class in the period between 1900 and 1917. Many persons who lived in apartments were able to buy homes for the first time. They selected sites in new housing plats in cities and suburbs (which were now accessible, thanks to interurban transit). To meet the market demand of this new population of homeowners, companies began to advertise in home decorator magazines to sell house blueprints or even "redi-cut" home kits. Kits were popular because they allowed new homeowners to buy their home in stages, a necessity since long-term mortgages were not available at this time. Catalogs of blueprints and kits could be mailed cheaply to potential buyers and kits could be shipped easily via railroad cars. Homes sold as kits represented the highest-priced single item ever sold by catalog retailers. Most catalog home companies were headquartered in the Midwest because of the plentiful supply of lumber.

It was no coincidence that bungalows were the most popular catalog home design. They were cheap to build, small and simple in design, and functional for first-time buyers because they often included built-in furniture. And they were heavily promoted. In its 1908 catalog Radford's Artistic Bungalows, the Radford Architectural Company of Chicago noted, "The bungalow age is here. It is a renewal in artistic form of the primitive 'love in a cottage' sentiment that lives in some degree in every human heart. Architecturally, it is the result of the effort to bring about harmony between the house and it surroundings, to get as close as possible to nature.... If any person intending to build a home is limited in his means, he cannot do any better than to build a bungalow." In the 1917 Aladdin Co. catalog, the "Sunshine" bungalow is described as having "individuality portrayed in all its lines and it is distinctively American in its character."

The catalog house was so popular that major mail-order companies that traditionally sold items like shoes, clothing, and underwear began selling homes around 1900. Sears and Roebuck of Chicago began selling building supplies in 1895 and complete house kits in 1908. They continued to sell homes until 1940, when they stopped because of financial difficulties experienced from a home mortgage venture begun just before the Depression hit. Montgomery Ward, another large catalog retailer, began selling house plans in 1910 and kits in 1918.

While the large catalog retailers are best known for their home sales, other companies were much more successful at it. One of the biggest was the Aladdin Company of Bay City, Michigan. It was founded in 1906 by two brothers, W. J. Soverign and O.E. Soverign, who got their idea from a Bay City company that sold pre-fabricated boats. Their first catalog was really just one sheet, and included a summer cottage that could be built for $300. Sales grew to $1 million by 1915, and peaked at $5 million in 1920. During its 77-year history, Aladdin sold more than 50,000 homes.

Aladdin's success was due largely to their innovative marketing techniques. To encourage buyers who were hesitant about committing large sums of money to a catalog company for a home, the company focused on quality, offering the "Aladdin Famous Dollar a Knot Guaranty." Every knot found in the wood by the purchaser could be refunded for $1. The company also promoted no waste in production, expert designers, the honesty and integrity of company owners, and endorsements from the likes of Saturday Evening Post as proof of their quality product. Advertisements also sold the dream of home ownership. Like all catalog home companies, Aladdin succeeded by taking high-styled homes to the people.

A look through any of the home catalogs soon reveals why these designs were so popular. Radford's 1908 catalog of 208 designs of the "best modern ideas in bungalow architecture" shows houses to fit nearly every taste. Design No. 5007, a two-bedroom home just 30 feet wide and 36 feet long, included a classical Greek colonnade across the front. Design 5039 looked like a miniaturized version of Frank Lloyd Wright's Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois. A complete set of plans for these houses ranged in price from $7 to $12, and most were estimated to cost between $1000-$2000 to build. Aladdin's 1917 catalog included full-color sketches of completed homes which showed blooming flower gardens and happy homeowners and their pets. Aladdin and others identified their homes with names meant to evoke feelings about the design-"The Castle," "The Venus," and "The Carolina," for example. It would be hard to agree with some of the name designations. "The Castle" was a five-room house with two 10'x10' bedrooms. It sold for $518.70.

Selected Item Descriptions

Gustav Stickley. Craftsman Homes, 1909.

Gustav Stickley produced catalogs of his Craftsman-style homes in 1909 and 1912. In addition to exterior views, the catalogs included interior designs, Stickley furniture, fabric and needlework patterns, and projects for home wood workers. A bungalow design from the 1909 catalog shows a simple country home with a second story dormer, a common feature that allowed light into the second story despite a long, low roof line. A fireside inglenook, kitchen cupboard, and window seat were built into the design.

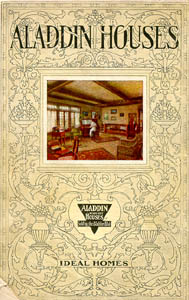

Catalog of Aladdin Homes. The Aladdin Company, Bay City, MI, 1917.

The Aladdin Company of Bay City was the first and most successful of the catalog home companies, lasting from 1906-1983. While nearly every home style was available from Aladdin, most until the 1930s were bungalows. Aladdin catalogs included full-color artist renderings of the most popular styles, and depicted the homes as they would look on-site so catalog customers could better imagine home ownership.

Radford's Artistic Bungalows: Unique Collection of 208 Designs of the Best Modern Ideas in Bungalow Architecture. The Radford Architectural Company, Chicago, IL, 1908.

Radford advertised itself as the Largest Architectural Establishment in the World. Unlike Aladdin, Radford did not sell kits, but rather building plans that could be purchased for as little as $7. This particular catalog included many Prairie-style homes, a design usually neglected by kit sellers because of the more complicated construction requirements.

Bilt Well Mill Work Catalog. The Collier-Barnett Co., Toledo, OH, ca. 1917.

While not selling complete home kits, companies like Collier-Barnett sold pre-fabricated architectural components of homes to builders. Builders could order doors, windows, moldings, staircases, and even built-ins from the company rather than build them on site, thus reducing construction costs. Many of the designs in this catalog included Arts and Crafts elements.

Back to the Book Arts  On to Interior Design

On to Interior Design

An Exhibit at the Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections, Carlson Library, The University of Toledo.

March 26th-June 30th, 1999.