On to America

On to America

Back to Introduction  On to America

On to America

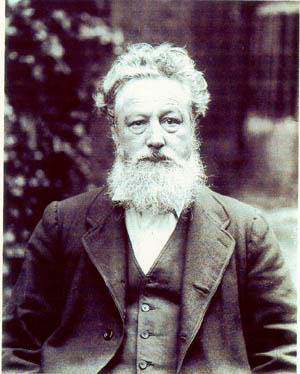

The Arts and Crafts Movement began in England in the 1860s as a reform movement. Its primary proponents were John Ruskin (1819-1900) and William Morris who is pictured at right (1834-1896). Ruskin, its philosophical leader, was the most influential of all Victorian writers on the arts and a member of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. The Pre-Raphaelites believed the medieval world was purer in form than the post-Renaissance world because it was more closely tied to nature. Ruskin's book The Stones of Venice (1853) had a great impact on the intellectuals of Victorian England. In it, he made a direct connection between art, nature, and morality-good moral art was nature expressed through man.

Continuing this connection, Ruskin believed the decorative arts affected the men who produced them. The machine dehumanized the worker and led to a loss of dignity because it removed him from the artistic process and thus, nature itself. As Ruskin stated, "all cast from the machine is bad, as work it is dishonest."

While Ruskin built the philosophical foundation of the Arts and Crafts Movement, it was William Morris who became its leader. Morris took Ruskin's ideas about nature, art, morality, and the degradation of human labor and translated them into a unified theory of design. By doing so, Morris successfully wedded aesthetics and social reform into the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Morris was appalled by the over-the-top ornamentation of Victorian design, especially its eclectic mix of styles. He was particularly disturbed by decorative arts produced by machines in mass quantity with no function but to decorate. This manufactured look was epitomized by furniture design known as "Eastlake." Charles Eastlake's name became synonymous with furnishings that copied ornate designs of earlier periods, but which were actually produced cheaply by machines. Eastlake himself was a reformer, advocating in his work Hints on Household Taste (1868) for a lighter form of decorative arts. Unfortunately, his name was forever tied to some of the worst examples of machined Victorian design.

Like Ruskin, Morris had a deep affection for the Middle Ages, especially the medieval idea of craftsmens' guilds. Along with architect Philip Webb, painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and others, he founded Morris & Co. in 1875. The guild was to create simple furniture, stained glass, and even wallpaper that united beauty, craftsmanship, and utility. He also founded the Kelmscott Press, a small book printing and binding company that became known for its outstanding examples of the book arts. He used the press to publish many of his own writings, thereby promoting the Arts and Crafts movement in both the content and style of the books.

But in all of his works, Morris believed that the Arts and Crafts Movement was much more than just a design theory. If the quality of design was improved, the character of the individual producing that design would be improved, and hence society would be improved. Here, Morris was clearly influenced by socialism. He observed the terrible working conditions of the factories, their environmental consequences on the surrounding countryside, and the exploitation of cheap labor that led to shoddy products. He believed society would be vastly improved by a return to the pre-industrial revolution days where craftsmen were both the designers and the manufacturers of products. Succinctly put, Morris sought to reunite "head and hand."

Morris was not wholly successful in translating the Arts and Crafts philosophy into a practical application. One of the most difficult obstacles was how to produce beautiful handcrafted items that could be affordable to the working classes. He never successfully overcame this problem, and most British Arts and Crafts items remained the luxury of the upper classes. But despite this, the Arts and Crafts movement swept England. Morris's disciples like C.R. Ashbee, Baillie Scott, and C.F.A. Voysey helped to form Arts and Crafts associations. Beginning in the 1880s, major exhibitions of materials identified as "Arts and Crafts" were held.

Selected Item Descriptions

Charles L. Eastlake. Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details. London: Lonmans, Green, and Co., 1868.

Eastlake, a renowned architect of Victorian England, also designed furniture and wrote on interior design. While he advocated for a more restrained, less embellished look, his name has become synonymous with machine-made, highly ornamented Victorian furniture. The Arts and Crafts Movement as envisioned by Ruskin and Morris was in many ways a reaction to Eastlake design.

John Ruskin. The Stones of Venice. New York: Hill and Wang, 1964, c1960.

The Stones of Venice with its chapter "The Nature of Gothic" appeared in 1853. The British Arts and Crafts Movement viewed this chapter as its sacred text. William Morris printed an edition of the chapter and described it as "one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century."

Morris was influential in inspiring the American Arts and Crafts movement in many ways, but especially through his book arts. His Troy (large Gothic), Golden (Roman) and Chaucer (smaller Gothic) typefaces were much admired. The Kelmscott Press achieved Morris's goal of books being "beautiful by force of mere typography." (On loan from the collection of Allan B. Kirsner).

The Tale of the Beowulf (done out of the Old English Tongue by William Morris and A. J. Wyatt). Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1895.

Another of Morris's influential editions, this one drawn from traditional English texts. (On loan from the collection of Stephen J. Farber).

Back to Introduction  On to America

On to America

An Exhibit at the Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections, Carlson Library, The University of Toledo.

March 26th-June 30th, 1999.