Introduction:

It was

called the most significant advance in the production of glass in 2000 years. It has been designated as an international historic engineering landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. In 1913, it received a

commendation from the National Child Labor Committee of New York City for reducing the need for child labor. It made possible the modern

distribution of many processed foods at greatly reduced costs. It provided a cheap and safe method for storing and transporting prescription

medicine. Without it, some of the country's major corporations, like Coca-Cola, might not have been possible. And without it, Toledo would not

have been the "Glass Capital of the World."

It was

called the most significant advance in the production of glass in 2000 years. It has been designated as an international historic engineering landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. In 1913, it received a

commendation from the National Child Labor Committee of New York City for reducing the need for child labor. It made possible the modern

distribution of many processed foods at greatly reduced costs. It provided a cheap and safe method for storing and transporting prescription

medicine. Without it, some of the country's major corporations, like Coca-Cola, might not have been possible. And without it, Toledo would not

have been the "Glass Capital of the World."

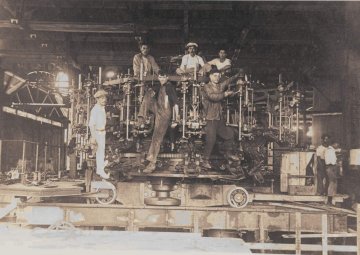

To the layman, the Owens Bottle Machine looks like a many armed monster. The complexity of its

engineering boggles the mind. The fact that it was invented by a man who lacked any formal education or technical training makes it even more

remarkable.

Michael J. Owens, who began working

in the glass factories in Wheeling, West Virginia, at the age of 10, learned glass manufacturing the hard way. He shoveled coal into the

furnaces, worked as a "carry-in boy" taking fiery hot blown bottles to the annealing lehr, as a "carry-out boy" taking cooled glass out, and as a

"mold hold boy" opening and closing molds for the master glass blower. The blower, who gathered a red-hot "gob" of glass from the furnace and

onto the end of a blow pipe, made bottles one at a time with the help of at least three boys like Owens.

While the automatic bottle machine is

incredibly complex, Owens's vision for a machine to do the job of all of these workers was not. As Owens conceived it, a gob of glass was sucked

into the top of a bottle mold through a rod that looked similar to a blow pipe, and as the piston reversed with a burst of air, it was pushed

down through the rest of the mold. Not only were child laborers no longer needed, but skilled glass blowers were also unnecessary. At the end of

the process, the bottle would be delivered to the annealing lehr by a conveyor belt. The first successful commercial model, produced in 1905,

could make 9 bottles a minute or nearly 13,000 a day and required two men per shift to operate. This compared to around 3500 produced

by hand in 24 hours by seven skilled men and boys. The machine dropped the cost of production from $1.80 a gross to 10 to 12 cents a gross.

What started as the vision of a man

with little education but much ingenuity has become an international corporation. It has spawned other technological innovations and major corporations that produce spun glass fibers and flat glass. While Edward Drummond Libbey brought the glass industry to

Toledo in 1888, it was Michael J. Owens, hired by Libbey at the age of 29, who made the industry in the city successful.

and major corporations that produce spun glass fibers and flat glass. While Edward Drummond Libbey brought the glass industry to

Toledo in 1888, it was Michael J. Owens, hired by Libbey at the age of 29, who made the industry in the city successful.

This exhibit showcases Owens's

invention, and the development of his company. It details how that company grew and changed, and its influence on the city and the world. I hope

visitors will leave with not only a greater appreciation for Owens, but with a better understanding of the importance of the glass industry to

our city. While our claim to be the "Glass Capital of the World" may be debatable today, the impact of the industry on our city's past and future

is not.

In May 2005, Dr. Timothy

Messer-Kruse, then of the UT Department of History, contacted Steven McCracken, president of Owens-Illinois, to suggest that the corporation

consider preserving its historical records in the Ward M. Canaday Center. Mr. McCracken agreed, and in September 2005, the collection arrived in

a semi-truck on 19 large pallets. Since that time, the staff, particularly Kim Brownlee, manuscripts librarian, have worked hard organizing the

nearly 500 feet of material. It includes a significant collection of historical bottles in addition to corporate records.

The Canaday Center, which also

preserves the historical records of Libbey-Owens-Ford, Inc. (now Pilkington North America), is one of the premier archival repositories in the

nation for studying the history of industrial glass. As you will see from this on-line exhibit, the Center's collections contain many amazing and

previously unseen items.

In addition to Ms. Brownlee, I would

like to thank other members of the Canaday Center's staff for their assistance with organizing the collection and exhibit: Casey Stark, Stephanie

Shook, and Ryan Eickholt, former graduate students employed in the Canaday Center; Tamara Jones, part-time librarian; and Sandy Rice,

administrative assistant. Greg Johnson, digital initiatives archivist, developed the on-line exhibit based upon the actual exhibit that was on

display in the Canaday Center in 2006. A special thanks to Ann Bowers, former director of the Center for Archival Collections at Bowling

Green State University, who served as a visiting researcher during the summer of 2006 at UT to help us complete the work on the exhibit and

catalog. While the Canaday Center and the CAC have often been rivals in their efforts to collect archival materials in the past, this project has

shown how valuable cooperation is to our profession. Also in the spirit of professional cooperation, Julie McMaster, archivist at the Toledo

Museum of Art, arranged for us to borrow several important items from the museum's archival collection for the exhibit. Jutta Page, curator of

glass at the museum, graciously agreed to be the opening speaker for the exhibit. I would also like to thank Dr. John Gaboury, the Dean of

University Libraries, for providing support for this massive project.

Sue Benedict of Photographix

designed the exhibit catalog cover and poster, and Liz Allen of Marketing and Communications designed the catalog. As always, these contributions

have made for a more powerful and interesting publication.

The book The Glassmakers: A History of Owens-Illinois, Inc., (Toledo,OH: The Trumpeting Angel Press, 1994) was invaluable to the

Canaday Center staff in researching and writing the catalog to this exhibit. We would like to acknowledge author Jack Paquette for his work, and

give him credit for much of the information you read in this publication.

Carol Gee, Lauren Dubilzig, and Kelley Yoder from the

Corporate Communications department of O-I have been extremely helpful in securing this collection and organizing this exhibit. The Canaday

Center appreciates the confidence shown by O-I in placing its valuable history in our care, and we take our work of preserving this irreplaceable

collection seriously. We hope that the vision of Mr. Owens expressed over 100 years ago will continue to be explored through the future research

produced from this collection.

Barbara Floyd

Director, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections

The University of Toledo

It was

called the most significant advance in the production of glass in 2000 years. It has been designated as an international historic engineering landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. In 1913, it received a

commendation from the National Child Labor Committee of New York City for reducing the need for child labor. It made possible the modern

distribution of many processed foods at greatly reduced costs. It provided a cheap and safe method for storing and transporting prescription

medicine. Without it, some of the country's major corporations, like Coca-Cola, might not have been possible. And without it, Toledo would not

have been the "Glass Capital of the World."

It was

called the most significant advance in the production of glass in 2000 years. It has been designated as an international historic engineering landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. In 1913, it received a

commendation from the National Child Labor Committee of New York City for reducing the need for child labor. It made possible the modern

distribution of many processed foods at greatly reduced costs. It provided a cheap and safe method for storing and transporting prescription

medicine. Without it, some of the country's major corporations, like Coca-Cola, might not have been possible. And without it, Toledo would not

have been the "Glass Capital of the World."